This is the second part of a larger piece of writing. You can read the first part here; I published it a few weeks ago, and it deals with the first two times questions were raised about why I set my book in the community I belong to when my biological ancestors came from elsewhere. This second part deals with the third time this happened. I think it warrants its own essay as these dynamics are different from the first two times it happened. I’ve also offered some thoughts on related issues in the arts. I held off posting this with respect to the health of the person it concerns. Now that she’s up and about again, it’s time to publish this final part.

–

My book Always Will Be was published on the 27th of February 2024. It’s had an overall positive critical reception from black, white and other settler reviewers, and I’m beyond grateful as nobody owes me love for my book, and I know no writer is entitled to even one, let alone multiple excellent and incisive reviews.

On the 29th of March the Australian Book Review published a short review by Claire G Coleman, another Aboriginal speculative fiction writer. I had met her briefly twice before many years ago but we never spoke in depth nor have we worked together, so she does not know me or my family.

Her review puzzled me for reasons I won’t get into here but I put it down to it being so short; after all I had also been commissioned in the same issue of ABR to review a book at 950 words and I assume Coleman was given the same limited word count. It was a tight squeeze and I don’t blame her for cashing it in.

But there is one line that I take issue with. I have bolded it below:

The work might have been more culturally powerful if Saunders had written stories of her own ancestral Country, the lands that first suffered the impacts of colonisation on this continent, but it is understandable to write about the community that has welcomed you, as communities in the Tweed of Always Will Be give sanctuary to people from other homelands.

On the surface this might seem like a small, innocuous comment, and maybe it appears like valid critique to the casual reader. Maybe it feels balanced and generous. This is not even the most critical aspect of Coleman’s review, but this is not an essay about sour grapes. It’s very simply a cultural matter, though for different reasons than Coleman has written. The problem is not only what is said but also who said it and how it was said. And just to make sure I’m not carrying on over nothing I’ve asked other blackfellas about this and all of them see the insult too.

This comment got me super riled up – and not least of all because I’d already belaboured this point in the book itself in my Bugalbeh, my thank you section (as well as in my story ‘A Prodigal Return’ which explores this kind of conflict in the future). Coleman either didn’t read my statement in the back of my book that goes over this ground already, or if she did read it she didn’t understand it. That’s why I want to talk about why this comment is wrong, why Coleman is not the right person to say it, and why this was the wrong forum to say it in.

If we’re going to have these conversations out in public, let’s lay all our cards on the table and have at it.

–

Coleman asserts that it would be more ‘culturally powerful’ to set my book in Sydney. I reject this. The crux of our conflict is that of nature versus nurture, of ancestry versus belonging. This argument goes much deeper than my annoyance with one line in one short review about my little book. It is in fact a cultural issue – and it’s a white cultural issue, because our people have figured this out already.

Black families, including mine, are connected through many forms of relationality. Cultural people know this. We are related in much more complex and nuanced ways than white genealogical trees that trace descent in a linear, blood quantum way. My strongest belonging is far more cultural than genetic, and here’s a brief background to fill you in.

First, the bare bones of a tragic and violent history: my Dharug great grandmother was stolen from her family and eventually both her children were stolen from her too. None of them were ever reunited, and I never met my grandmothers either.

Next, some maths: I was born in 1984 in Sydney, where my grannies were stolen from and never returned. My family moved to Tweed in 1994. That’s 10 years in Sydney, 20 years mostly in the Tweed, and the next 10 all over the shop – Melbourne, Sydney, and no fixed address.

Finally, some happily ever after: I grew up in a Koori and Goori family in the Tweed. My stepdad’s dad, Pa, was a Bundjalung and South Sea Islander man, and a respected elder in our community. He accepted me as his granny. We don’t share any blood but he is one of my ancestors now, as are his old people too. My youngest (biological) brother is my stepdad’s son. My oldest (adopted) brother was Bundjalung and South Sea Islander too.

To summarise: I am a Dharug descendant, yes, but I never knew my Dharug grandmothers. Neither of them or my mother or I belong/ed to the Dharug community. We all belong/ed to other Aboriginal communities. I belong to a Bundjalung family and the Tweed Goori community. This is why my writing is set there.

Now listen up. I’ve lost track of how many jobs and other opportunities I’ve turned down for ethical reasons – many because I felt they belonged to a Dharug person, and others because I felt they belonged to a Bundjalung person. I have been turning these jobs down for years because there are other writers and speakers better placed to do these jobs. So, what work can I do then? From what place can I speak?

Well, I’m certainly not going to resort to pan-Indigenous, flat and tropish stuff that sidelines specific histories and elides nuance. But by what right do I have to speak on Dharug issues, four generations removed? I won’t pretend to know more about my ancestral culture than I do, and it would be fraudulent to pretend I can speak for the contemporary Dharug community.

All I can do is write what I know, which is where my cultural knowledge is situated. As one example, all the Bundjalung language I know I learned in my home, in my school and on the streets. Not from a dictionary or a TAFE course, and not on the Internet. My identity precedes my social media presence by decades. From birth! It precedes my writing career by decades too, including applying for grants, fellowships and identified positions.

And this is why I feel sure of my decision to write fiction set in my community even though my DNA didn’t originate here. Belonging to a living, land-based family is much more culturally powerful than identifying with distant, unknown and unknowable ancestry.

Can you see how seriously I take this stuff? I’ve had a whole lifetime to think about it, unlike some.

–

Coleman’s small comment reads as though she is an authority on Aboriginal culture, which doesn’t fly given her history. Although Coleman is ten years older than me, culturally she is decades my junior, so let’s look at how very cheeky it is that she is holding forth about cultural power.

Born in 1974, Coleman grew up thinking she had Fijian heritage. By her own reports she found out she had an Aboriginal ancestor well into her adulthood – in her early 30s, according to my maths, well past her formative years.[1] She’s spent most of her life in Melbourne (since 1996) but from my inquiries she does not belong to the Naarm Koorie community, nor has she ever lived with the Noongar community of her ancestry. From her own testimony, she and her father found out about their ancestor at the same time, so they’ve been learning of their history together (not her learning from him), and neither of them knew their Aboriginal relatives while they were alive and identified as black. So, no cultural elders to learn from then or now. This is a sad story, and all too common. I feel for the family on their journey of reconnection.

Whether Coleman began identifying as Aboriginal immediately or not is a mystery. I’ve personally known quite a few people who’ve found surprise Aboriginal ancestry in adulthood, or else they’ve had vague family rumours confirmed. Most of these people just accepted this new knowledge and went about their lives as before, while some chose to take it further. No judgement either way, but of the blackfellas I do know and vibe with who came into their identity late, they’ve all embarked on a slow and respectful period of discovery and reconnecting. This can be a long and winding road to choose, full of mistakes and hard lessons. Frustrating as well as rewarding. Mostly done in private. There is usually a lot of learning that comes between finding an ancestor and potentially becoming one – but I am unsure at what point this occurred for Coleman in the 9 years between discovering her ancestry in 2006, and writing her debut novel Terra Nullius in 2015, which then won the lucrative Black&Write! Indigenous writing fellowship the following year.

Moving beyond her ‘cultural power’ arbitration, Coleman’s entire review is therefore a trick: throughout it, she adopts the pronouns “we” and “us” to talk about “our” culture. These first person collective pronouns are deceptive, as though we share similar experiences. Respectfully, we do not.

Somewhere along the line, Coleman chose to be black.[2] Well good for her, but most of us don’t have a choice, and it is an insult to suggest that a simple choice she made well into adulthood weighs as much as my entire four decades of living and all that growing up and learning entails.

We only learn culture through living relationships to cultural people – the good, the bad and the ugly – and investing in our relations over our lifetimes, as we are invested in too. We don’t just learn what culture is (food, language, music) but how to practice it too (ways of thinking, feeling and relating). All the stuff below the surface. Culture is learnt by immersion – watching and doing with living people – not by magpieing others through reading stories or articles, or consuming media. You simply cannot learn to be cultural from books or the Internet, or from people you sometimes work with – from those who are paid to be nice to you. Anyone who thinks they’ve learnt culture this way is performing minstrelsy. As someone who isn’t Bundjalung I’ve thought about this stuff all my life, and much more thoroughly than Coleman has.

Implicit in Coleman’s comment is that we should only write characters who align with our ancestry, which brings up some interesting stuff in relation to her oeuvre. As a scholar of First Nations speculative fiction I’ve read most of Coleman’s fictional work. I also used to follow her on Twitter. Across her three novels and many other shorter stories she has written teenage blacks, cultural blacks, dark skin blacks, Naarm community blacks, Arrente blacks, and other desert blacks from anonymous homelands – none of which she is now or ever has been. To my knowledge she is yet to write a white-passing character who began identifying as Aboriginal later in life. From both her body of work and her social media posting it is clear she has insecurities around her identity and skin colour.[3]

I haven’t been able to find the specific context, if any, where Coleman’s cultural knowledge is situated. Yet she states on her website that she’s been a cultural advisor for an Indigenous arts organisation since mid-2020.[4] This is obscene considering she’d only identified for somewhere between 5 and 14 years at that time. All of my teenage nieces and nephews have been Aboriginal for longer.

This is really wild stuff. Let me offer an analogy from my own life to show you. One of my great grandfathers was Irish. He was born in the old country and came here last century. He died just before I was born, so we never met. Still, I know the county he came from and our family name – I’ve known this all my life – but despite this, I don’t go around claiming I’m Irish. See, I don’t belong to an Irish community nor do I have a connection to the people beyond mainstream offerings of Irish stories and culture, but this doesn’t count because the same is on offer to everyone. Can you imagine if, at the ripe old age of 40, I began applying for Irish fellowships, grants and positions, and acted as an arbiter or gatekeeper of Irish culture and identity?

I’ll stop being glib now and offer another analogy to talk culture, closer and more serious this time. I am also Lebanese. My dad, my situ and jiddo, my many aunties, uncles and cousins – all of them are too. Lebanese was one of my two first languages, Aboriginal English being the other. I no longer speak it fluently but very brokenly, though I do still understand it somewhat, sometimes. I’m still close to my Lebanese family though we don’t see each other often. I’ve been part of Lebanese ceremonies of marriage, christening, death and mourning. Lebanese food is my comfort food. All this is to say that I am connected to Lebanese culture, and I have been all my life. But enough to claim expertise on it? No way. I would be ashamed to claim that, and if someone offered to retain me for my expertise I would pass the opportunity on to someone much more immersed in the day-to-day.

–

The first two times this issue came up the querents approached it in gentle ways, having had little to no context to go off, and neither my thesis examiner’s report nor the Unaipon judges citation were public until I published the first part of this essay. This time? Coleman misstepped by saying something she had no business saying in such a public forum.

If we wanna talk about cultural ways, here’s a start: don’t impugn the cultural integrity of a lifelong black writer in a literary magazine catering to rich white arts patrons. Or, if you do, expect to be taken to task. This is culture.

As blackfellas, we must respond to questions about our belonging head on, as I have done over my lifetime. And as Coleman’s question is in a public review of my work, I’ll respond in kind. I can’t control whether my work is enjoyed or how it is understood, nor do I want to. But if anybody wonders out loud about my right to write it, I’ll take my right of reply. This is a matter of pride and integrity. ‘Cultural power’, if you will. I’m not someone who goes looking for fights, but I was brought up by Kooris, Gooris and Lebs who never shied away from conflict, and I’m a real chip off those old blocks for sure. If anyone wants to make a dig at me or about me, I’ll address it directly, no matter who the other person thinks they are. I’m not intimidated by anyone except for maybe one of my aunties.

Part of “our” culture is getting growled at when you fuck up, and the most cultural way forward from a mistake is to just cop to it, right on the chin, and learn your lesson. It remains to be seen how ‘culturally’ this will play out. And in anticipation of any intellectually lazy responses: Coleman is not from my community so this is not ‘lateral violence’, and she’s an established author publicly styling herself as a cultural authority when she isn’t, so this is not ‘punching down’.

A big reason I wrote this essay is to correct the record. When I imagine the younger people in my family reading my book years down the track, and maybe seeking out reviews to see how it was received at the time, I imagine them reading Coleman’s review. Possibly wondering if she’s right – and maybe thinking she has the right to say it. Wondering how this affects their belonging to the Tweed too. My skin is crawling thinking about it. So what I’m doing here is returning the favour – opening this discussion up so that any young people in her family might consider my reply if they ever go digging for responses to her work too.

Ultimately, I wish all newly-identifying blackfellas nothing but the best on their personal journeys of reconnecting and discovery. I just ask that they watch where they step on the way.

–

Another reason I wrote this is because I want the literary and arts world to think about cultural matters more deeply and more logically. I’m writing this in the hopes that anyone who has any power over Aboriginal writing – publishers, editors, judges, reviewers – can consider that belonging is much more complex than simple blood quantum or distant ancestry would have you believe.

I do realise that this whole thing might read as though I have it in for one writer specifically, but I don’t even know Coleman so it’s nothing personal. This is just unfortunately part of a dense matrix of interconnected issues that’s made me want to rage quit the arts and literary industry many times in the few short years I’ve been part of it. Coleman’s mistake is just the latest in a long line of related stuff. And as she chose to be a culture cop in such a public and direct way, this is the perfect exemplar to talk about these broader systemic issues in the arts.

I have seen the many ways that identity is weaponised and used to grift or gatekeep, by Arts Aborigines especially. These are the ones who find community through work – which is fine as a complement to a living, land-based community but it cannot replace or stand in for or be mistaken for the same. Without their jobs and social media, Arts Aborigines have no community to speak of, and it shows in the damage they do.

I’m about to rattle off a list. Bear in mind that each and every one of these examples have multiple guilty parties I’m aware of – hence the plural nouns – and I’ve only been in this industry for 5 years. Imagine, then, the true scope of things!

So: I have seen real Aboriginal writers passed over for life-changing opportunities for those who only allude to be; Aboriginal artists who are disconnected from culture being paid as experts on these matters; Aboriginal writers who grew up white suddenly cosplaying our identities by speaking lingo in their videos and wielding their new accents like bludgeons; newly-black scholars writing Aboriginal books as though they have the right, and making good money off it; those who grew up white touted as experts on our storytelling ways; I’ve read stories and reviews by people who cannot name their country or community yet write of culture, as if you can have culture without them; Aboriginal artists who grew up wealthy, who’ve never known hard living or been targeted by cops making big money from our tragedies; there are writers from one nation trading in the stories of other nations that they have no relationship to. As these writers and artists never give anything back to the people they take from, these are just new forms of exploitation and profiteering. And guess who loses out?

I feel a moral obligation to other community blackfellas, who our awards and grants are designed for – who our elders had in mind when they fought for these gifts – to pick these issues apart, to speak on matters of identity and belonging from my own considerable and well-examined lived experience. I urge others think about identity as belonging – not as choice, but as lived in and embodied. Not made up in the mind.

And look, I agree that identity and belonging are very valid things to question, but there are much more elegant, good faith ways to do it. You know, judging or evaluating writing is hard enough as it is. Sometimes the winners of competitions are clear and decided unanimously, but often it’s the best compromise between the judges. But when it comes to judging cultural appropriateness and protocols for determining it, in my experience, settler judges and Indigenous ones alike can be just as clumsy as each other. It makes an already complicated process even more fraught. But usually some gentle questioning and asking around can clear things up. For my own part in this, I have definitely questioned other Aboriginal people’s identities before – but not yet in a public way until now. Every time I’ve had to question others as part of my job I’ve done it in respectful ways, not as a self-styled arbiter of culture. I’ve asked, not told.

Reviewing can be tough too, especially in such a small literary ecosystem as ours. I have critiqued some of the most beloved work of some of our most popular writers, on the record. My rule of thumb is that whenever I’m being critical to make sure it’s something I’d say to the person’s face, as our industry is so small; it’s even smaller if you’re a blackfella. I make sure I give good reasons for anything I say. It’s called rigour.

At the beginning of Part 1 of this essay I mentioned that writing this could be a matter of my livelihood, as could not writing it. This is not hyperbole. I know of another blackfella’s manuscript that was kept out of a competition because the black judges deemed the writer unfit to write on the community that he comes from. It was eventually shown that the judges were wrong but nothing could be done about it. On the other hand, some of my friends and colleagues have been blocked from opportunities because they’ve critiqued the gatekeepers. I know of many other instances where judges, publishers and reviewers wielded their power wrongly too. I wonder how many times this has played out for other mob I don’t know about. Maybe even my own work. I’ll never know.

–

The important thing, I remind myself, is that each of the three times this issue has been raised about my book, it’s been people from outside my community who have no connection to me bringing it up. I have never been questioned by people from my community. I have only been cheered on and supported, including by fellow Tweed Breed journalist Daniel Browning, who is truly the best there is in this poxy colony and beyond it.

At a more grassroots level, it’s now nine months post publication, and I’ve had the pleasure of talking with many Tweed mob about my book (including traditional owners) whenever I’ve gone home, if it ever happened to come up in conversation (I’m not very good at bignoting my achievements to my people). Everyone has so far been stoked about my book and if they’re not, that’s news to me. To be fair, I’ve never held a community wide meeting to ask everyone’s consensus, nor have I asked every Bundjalung person I know for their blessing. I did tell my stepdad about this whole thing but I won’t repeat what he said.

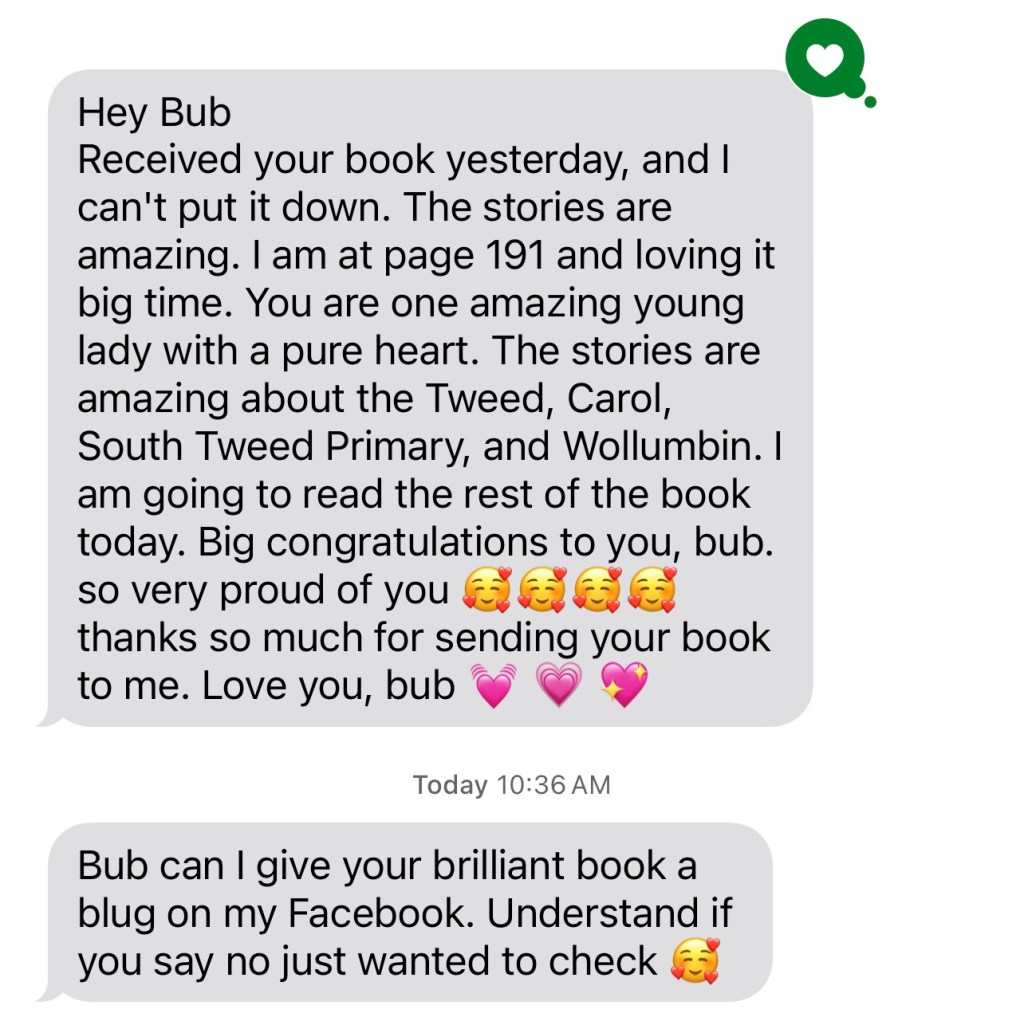

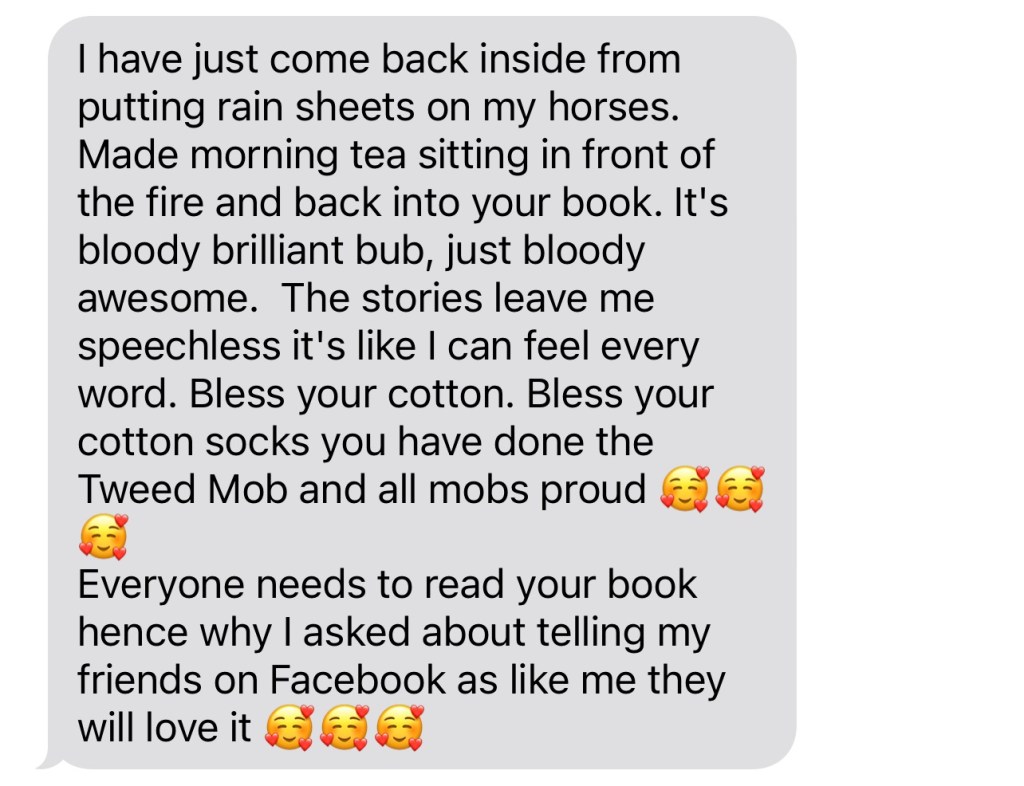

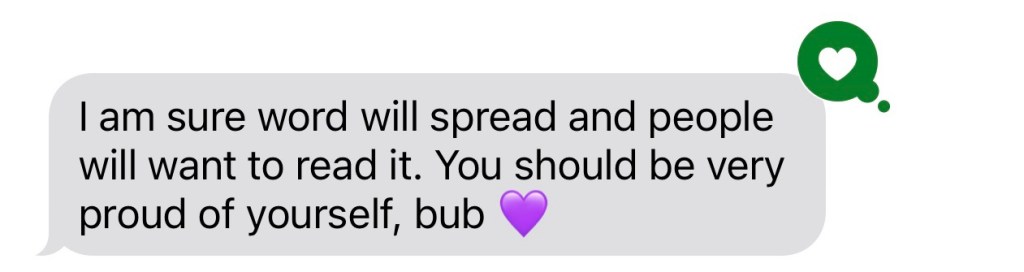

I am grateful my stories have won prizes and that my book has been well-received by the literary community, but the best prize by far is stuff like this:

These beautiful texts are from my Bundjalung and South Sea Islander aunty, my stepdad’s sister – and one of the only people in the world who frighten me a little bit. I’m sure you can see she could not be prouder of me. This, for me, is true cultural power.

Maybe in future editions of my book I should place these texts upfront in the acknowledgments page for anyone questioning my right to write these stories.

[1] To get my head around Coleman’s trajectory, I listened to Claire G. Coleman’s many lives, her 2020 interview with Richard Fidler.

[2] In her Guardian essay Not quite blak enough: ‘The people who think I am too white to be Aboriginal are all white, Coleman first writes that “Nobody gets to choose their race”, but then, a few paragraphs down, says: “Colonisers often ask me why I don’t identify with my Irish and English ancestry, why I prefer to identify with my Aboriginal family. There are many reasons – all of them, to my mind, compelling. The first is the simplest: if you could identify with the bully or the victim, with the murderers or the family of the murdered, with the genocidal colonisers or the colonised, who would you choose?” (Emphasis is mine.)

[3] I’ve chosen to edit out all the examples as I don’t want to detract from the point of my essay. This information is all publicly available for those who care to look, and I still have receipts too.

[4] “Since mid 2020 Claire has been a member of the cultural advisory committee for Agency, a Not-for-profit Indigenous arts Consultancy (https://agencyprojects.org/).”